Key points:

- The difference at RBW is that they're not trying to exploit a deposit

- They're trying to design a technology that can be applied to many deposits

- If it works – the chemistry is fine, it's the economics – then it could get very big

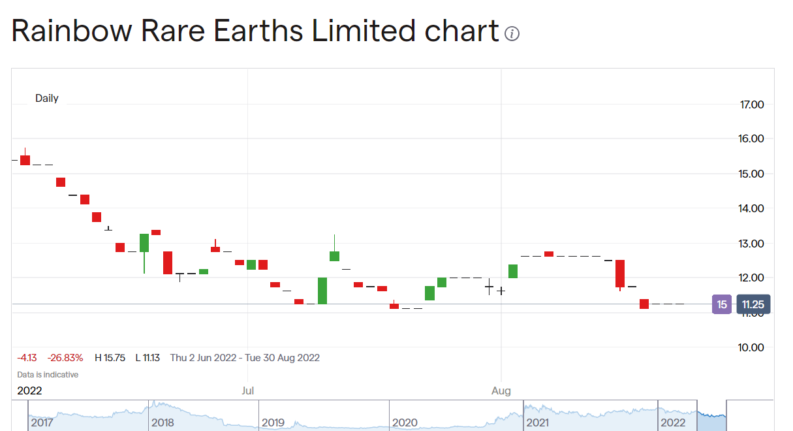

Rainbow Rare Earths (LON: RBW) is an interesting example of a small company doing many of the right things in a fashionable area – but no one seems all that interested. It could, of course, simply be that doing the right things in this field is not, in fact, fashionable. Or the risk in developing the right approach is seen as too high. Or even, given the information flow about small companies, no one is really aware as yet.

That the world needs more rare earths is obvious – that EV revolution isn't going to happen without magnets made from them. The thing is that rare earths aren't in fact all that rare. There are many different mineral sources of them. The big and better known companies – Lynas, MP Materials – extract from large deposits of the most common such minerals. Others, like Pensana, are developing similar systems and adding the separation plant – as Lynas has – to the system.

The thing is though it's possible to gain rare earths from many different mineral streams. And as a logical postulate it's cheaper to go and get a mineral when someone else has already done a lot of the work for you. That is, the wastes of other processes can be cheaper sources than digging your own hole in the ground. This isn't certain, it depends upon which wastes and so on. Also, the volume that can be achieved. But it's certainly something worth investigating – are there waste piles which are cheaper to separate than digging new mines?

Also Read: How To Invest In Metal Stocks

This is exactly the thinking behind Rainbow Rare Earths. It's long been known that there are rare earths in the phosphogypsum byproduct of phosphate mining for fertilisers. It's also a waste which people would like to do something with – it's lightly radioactive and perhaps not what we want blowing around the place as dust. If it could be cleaned up then it could become gypsum for plasterboard (sheetrock to Americans). And cleaning it up would have the effect of extracting the rare earths as well. Or, the other way around, extracting the rare earths would clean up the gypsum.

This could work – technically definitely it works – it's a matter of economics. So, this is what Rainbow is doing. They're working in South Africa to start with. Well, OK, so what?

The so what is that mining divides into two strands. Say you find a deposit and exploit it. Well, OK, but your success is defined by the size of the deposit. But if you create a new extraction technique then the whole world is ready to be explored for more instances of where the technique can be used.

And that's the point of today's announcement:”Rainbow Rare Earths (”Rainbow”) announces that it has entered into a Master Agreement (“Agreement”) with OCP S.A. (“OCP”), the Moroccan world leading producer of phosphate products,” The Moroccan industry is vast. So, the technique isn't only applicable in South Arica but can scale, massively. And after that there's the Florida industry to go for.

This is not, of course, proof that Rainbow has a useful or economic technique as yet. The point is though that if they do then they've got vast expansion opportunities in front of them. If they do prove their technique RBW could get very interesting indeed.